It's Time For 3D Printing To Evolve From The Hobbyist Market

- Charles Edge

- Apr 21, 2022

- 9 min read

The Apple II, Commodore PET 2001, and TRS-80 are known in computer history as the 1977 Trinity. The release of these computers signaled a turning point in personal computers. Computers were no longer just for big companies, they were now for use in the home. We're getting closer and closer to that state for 3d printers. This makes it an attractive investment thesis, even when we don't see many presentations to invest cross our desks. Yet we have 4 printers in our office!

How we got here

The style of 3d printing mostly done today has been around since the early 1980s. Chuck Hull and Dr Hideo Kodama each patented a technique in 1980 and 1981 respectively. A third company, Stratasys, developed Fused Deposit Modeling, or FDM and patented that in 1989. The FDM patent expired in 2009. In 2005, a few years before the FDM patent expired, Dr. Adrian Bowyer started a project to bring inexpensive 3D printers to labs and homes around the world. That project evolved into what we now call the Replicating Rapid Prototyper, or RepRap for short.

RepRap evolved into an open source concept to create self-replicating 3D printers and by 2008, the Darwin printer was the first to use RepRap. As a community started to form, more collaborators designed more parts. Some were custom parts to improve the performance of the printer, or replicate the printer to become other printers. Others held the computing mechanisms in place. Some even wrote code to make the printer able to boot off a MicroSD card and then added a network interface so files could be uploaded to the printer wirelessly.

There was a rising tide of printers. People read about what 3D printers were doing and wanted to get involved. There was also a movement in the maker space, so people wanted to make things themselves. There was a craft to it. Part of that was wanting to share. Whether that was at a maker space or share ideas and plans and code online. Like the RepRap team had done.

One of those maker spaces was NYC Resistor, founded in 2007. Bre Pettis, Adam Mayer, and Zach Smith from there took some of the work from the RepRap project and had ideas for a few new projects they’d like to start. The first was a site that Zach Smith created called Thingiverse. Bre Pettis joined in and they allowed users to upload .stl files and trade them. It’s now the largest site for trading hundreds of thousands of designs to print about anything imaginable. Well, everything except guns.

Then comes 2009. The patent for FDM expires and a number of companies respond by launching printers and services. Almost overnight the price for a 3D printer fell from $10,000 to $1,000 and continued to drop. Shapeways had created a company the year before to take files and print them for people. Pettis, Mayer, and Smith from a maker space called NYC Resistor also founded a company called MakerBot Industries.

They’d already made a little bit of a name for themselves with the Thingiverse site. They knew the mind of a maker. And so they decided to make a kit to sell to people that wanted to build their own printers. They sold 3,500 kits in the first couple of years. They had a good brand and knew the people who bought these kinds of devices. So they took venture funding to grow the company. So they raised $10M in funding in 2011 in a round led by the Foundry Group, along with Bezos, RRE, 500 Startups and a few others.

They were acquired by Stratasys in 2013 for $403M, who if we remember were the original creators of FDM. Pettis and the other makers left after a time and MakerBot become much more about additive manufacturing than a company built to appeal to makers. And yet the opportunity to own that market is still there.

This was also an era of Kickstarter campaigns. Plenty of 3D printing companies launched through kickstarter including some to take PLA (a biodegradable filament) and ABS materials to the next level. The ExtrusionBot, the MagicBox, the ProtoPlant, the Protopasta, Mixture, Plybot, Robo3D, Mantis, and so many more. Some Kickstarter projects are for collections of designs, others for printers. It can be hard to navigate through it all when first starting out.

Meanwhile, 3D printing was in the news. 2011 saw the University of Southhampton design a 3d printed aircraft. Ecologic printing cars, and practically every other car company following suit that they were fabricating prototypes with 3d printers, even full cars that ran. Some on their own, some accidentally when parts are published in .stl files online violating various patents.

Ultimaker was another RepRap company that came out of the early Darwin reviews. Martijn Elserman, Erik de Bruin, and Siert Wijnia couldn’t get the Darwin to work so they designed a new printer and took it to market. This is similar to how some open source operating systems are born. After a few iterations, they came up with the Ultimaker 2 and have since been growing and releasing new printers. David Braam from Ultimaker open sourced the slicing tool they built for the platform called Cura, which is now one of the best tools to slice, provided a profile exists for a given printer (these are not universal).

A few years later, a team of Chinese makers, Jack Chen, Huilin Liu, Jingke Tang, Danjun Ao, and Dr. Shengui Chen took the RepRap designs and started a company to manufacturing (Do It Yourself) kits called Creality. They have maintained the open source manifesto of 3D printing that they inherited from RepRap and developed version after version, even raising over $33M to develop the Ender6 on Kickstarter in 2018, then building a new factory and now have the capacity to ship well over half a million printers a year.

The future of 3D Printing

We can now buy 3D printing pens, over 170 3D Printer manufacturers including 3D systems, Stratasys, and Creality but also down-market solutions like Fusion3, Formlabs, Desktop Metal, Prusa, and Voxel8. There’s also a RecycleBot concept and additional patents expiring every year.

There is little doubt that at some point, instead of driving to Home Depot to get screws or basic parts, we’ll print them. Need a new auger for the snow blower? Just print it (there are already designs on Thingiverse for an Archimedes screw that could easily be tailored to that purpose). Cover on the weed eater break? Print it. Need a dracolich mini for the next Dungeons and Dragons game? Print it. Need a new pinky toe. OK, maybe that’s a bit far. Or is it? In 2015, Swedish Cellink releases bio-ink made from seaweed and algae, which could be used to print cartilage and later released the INKREDIBLE 3D printer for bio printing.

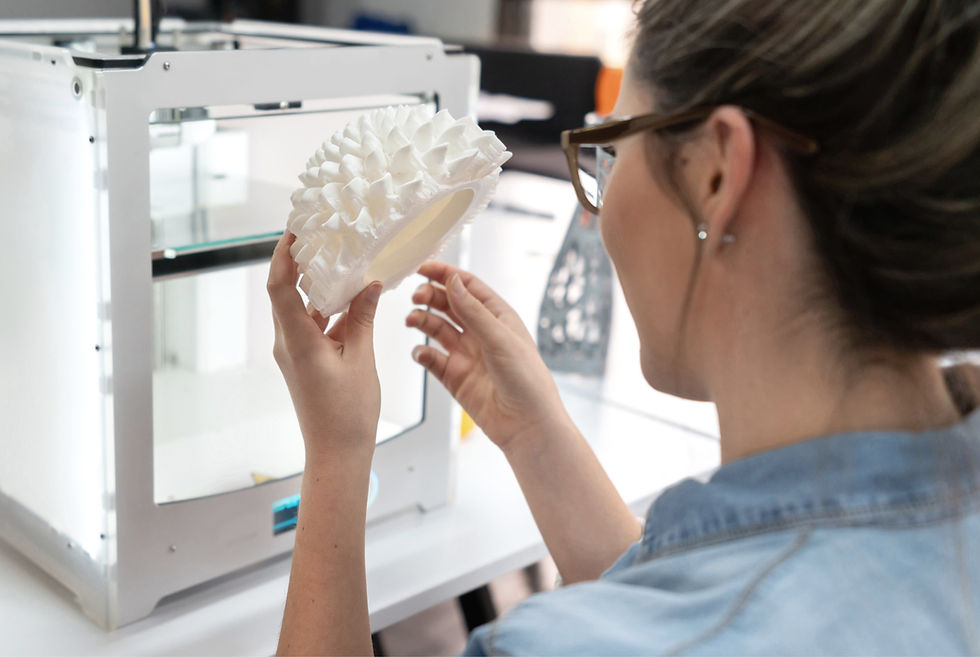

The market in 2020 was valued at $13.78 billion with 2.1 million printers shipped. That’s still half the number of devices the 1977 Trinity shipped in aggregate, but expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 21% for the next few years. But a lot of that is healthcare, automotive, aerospace, and still prototyping. There are plenty of companies like architectural firms that print their models. But anyone who has used a printer knows that it can take a few possessor a print to work out. Maybe the print file needs supports (gravity is a thing, so as a printer lays down a layer if there’s nothing to support the layer it can droop for areas where there’s an angle greater than 90 degrees), maybe the printer runs out of filament, maybe it isn’t level. This means not just anyone usually prints their designs.

Apple made the personal computer simple and elegant. But no Apple has emerged for 3D printing. Instead it still feels like the Apple II era, where there are 3D printers in a lot of schools and many offer classes on generating files and printing.

3D printers are certainly great for prototypers and additive manufacturing. They’re great for hobbyists, which we call makers these days. But there will be a time when there is a printer in most homes, the way we have electricity, televisions, phones, and other critical technologies. But there are a few things that have to happen first, to make the printers easier to use. These include:

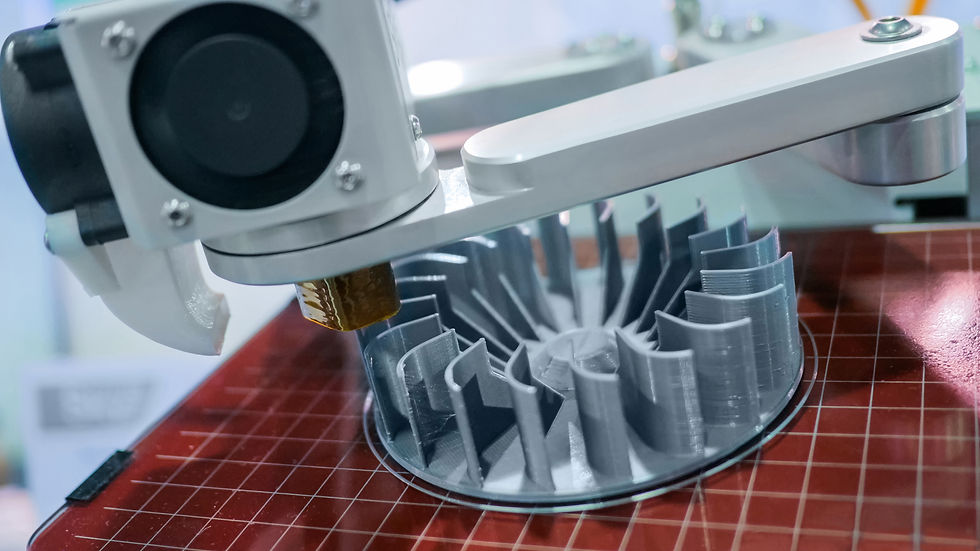

Every printer needs to automatically level. This is one of the biggest reasons jobs fail and new users become frustrated. Many printers now have beds that move, so adding a z-axis (up and down) to each corner is not a lot of additional circuitry and engineering. Most people should make this a must when buying a printer.

More consistent filament. Spools are still all just a little bit different. Using the same type of filament and keeping it dry helps keep jobs running smoothly. Having said this, there are a lot of great additive filaments, with metals and wood fibers that help make the things we print look more real.

Printers need sensors in the extruder that detect if a job should be paused because the filament is jammed, humid, or caught. Printers could also detect if filament isn’t being applied properly and stop a job so rouge filament doesn’t get into mechanical areas of the printer that could break it.

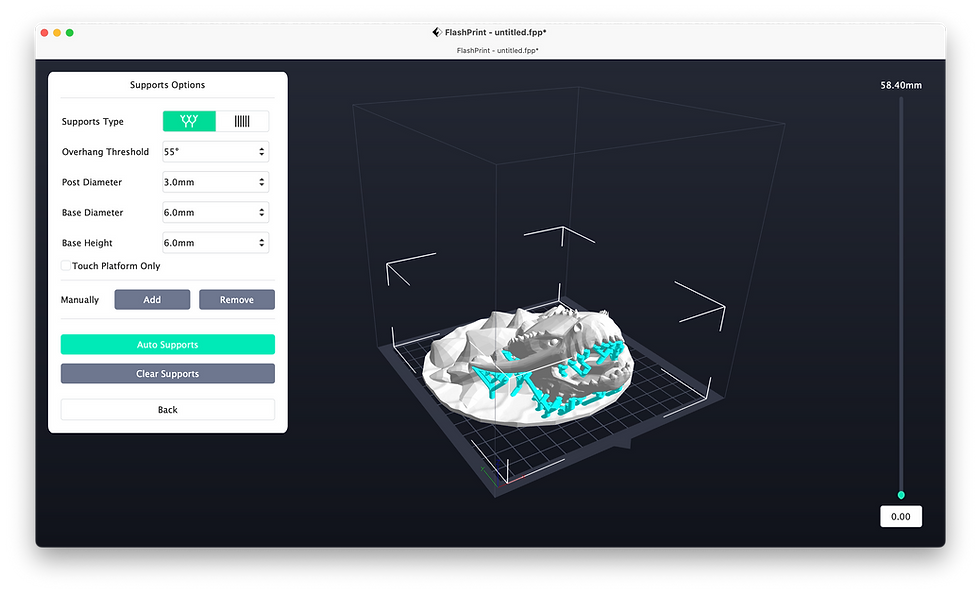

Automated slicing in the printer microcode that senses a .stl, the filament, and slices a job. We currently have to bring an stl file into an application used to “slice” it, or prepare it for the printer. Some of these applications provide a feature for supports, which is a way to build a structure to solve the gravity problem mentioned earlier.

Better system boards (e.g. there’s a tool called Klipper that moves the math from the system board on a Creality Ender 3 to a Raspberry Pi). Higher end printers have better screens and better boards, but don’t provide access to the solid state storage used on printers.

More standards from independent standards bodies. We have the ability to configure a printer in a tool like Cura by defining the codes Cura sends for various instructions to the printer. If these were all true standards (e.g. from ISO or IEEE) then vendors could more easily work with one another. Some work has been done but typically in manufacturing rather than general consumer use.

Cameras on the printer should watch jobs and use TinyML to determine if they are going to fail as early as possible to halt printing so it can start over.

Most of the consumer solutions don’t have great support. Maybe users are limited to calling a place in a foreign country where support hours don’t make sense for them or maybe the products are just too much of a hacker/maker/hobbyist solution.

There needs to be an option for color printing. This could be a really expensive sprayer or ink like inkjet printers used at first. Added benefit is that an ink jet could hide striations in print jobs. We love to paint minis we make for Dungeons and Dragons but could get amazingly accurate resolutions to create even cooler things with automated coloring.

Duplication technology should be built into printer apps. For example, we can use a number of different lidar scanners on an iPhone to create a 3d model. To migrate that to an stl file, then a gcode file can be cumbersome at best and plenty of fidelity is lost along the way.

The design market place space needs to get cleaned up. There are a number of sites that integrate with Thingiverse and other repositories of .stl files. It's possible to find most anything one could want and tweak it to a specific use case; however, there's a lot of clicking around where it isn't necessary. A clear leader that could send a job directly to a printer queue without slicing would be quite interesting.

The last bullet brings us to the biggest thing: user experience. 3d printing, even with better printers, still feels like a hobby market. We can use the same tools we use to create video game characters, like Blender, to create .stl files. But to take that .stl file and prepare it to be 3d printed requires work. Perhaps that’s dropping it into an app like Wiibuilder for the Weebo printers or FlashPrint for the FlashForge printers. If we had to create a postscript file in Word we likely wouldn’t print much on laser printers. Cura from Ultimaker does a lot of this for people but it’s still extra steps/clicks that aren’t necessary. There should just be a print button in a tool like Blender and the print preview should have an option to add supports or scale a job up and down if it exceeds the boundaries of a print plate.

For a real game changer, the RecycleBot concept needs to be merged with the printer. Imagine if we dropped our plastics into a recycling bin that 3D printers of the world used to create filament. This would help reduce the amount of plastics used in the world in general. And when combined with less moving around of cheap plastic goods that could be printed at home, this also means less energy consumed by transporting goods.

To summarize, the 3d printing technology is still a generation or two away from getting truly mass-marketed. The technology is useable in environments where there are people who have time to mess around with printers, like hobbyists or where it's part of a job. However, it is at the precipice of being useful to anyone interested in printing, the way the Apple III was ready to become the Mac. This is where 3d printing could change the very nature of ownership. It's easy to imagine giving anything we own away, because we might just print a replacement real quick. Or send a file to someone. Or scan a part on a car (like a gear or a hose), print a replacement, and pop it in. This brings up plenty of interesting questions around the patent status of, for example, that hose. Although Apple proved that if a song is a buck it takes less time to steal it - the same will likely become true for things we want to print.

Most hobbyists don’t necessarily think of building an elegant, easy-to-use solution because they are so experienced it’s hard to understand what the barriers of entry are for any old person. But the company who finally manages to crack that nut might just be the next Apple, Microsoft, or Google of the world.

Comments